A decade ago, a muscle physiologist named Brendan Gurd published a study comparing sprint exercise to longer continuous endurance exercise. Some responded best to the intervals; others responded best to continuous practice. The explanation was clear: to get the best training results, you need to find out what type of exercise you respond best to.

These findings fit with a broader push in sports science to move beyond “average” responses and provide personalized training advice that would optimize each individual’s response. But last month, Gurd and his colleagues at Queen’s University in Canada published another paper, the culmination of a long journey in which they concluded that they were wrong—that the individual change they saw in that 2016 study was a sham.

Their new findings, which mirror the results of numerous studies from many research groups around the world studying both strength and endurance exercise, are difficult for scientists and athletes (and frankly, journalists) to accept. After all, isn’t it obvious that some people get more bang for their workout buck than others? Even Gurd struggles with the idea: he’s a cyclist, and he sees riders on his regular group rides who seem to respond more than others to the same training advice. But the data says otherwise.

Respondents and non-respondents

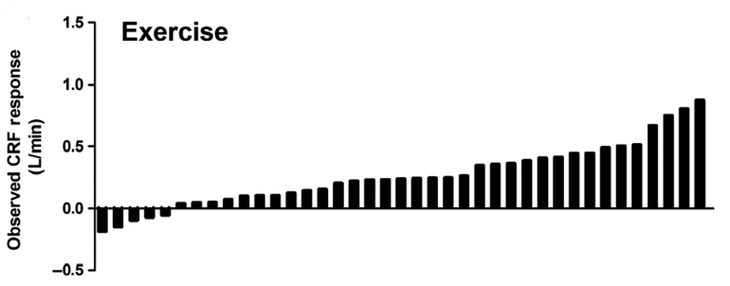

One of the big trends in sports science when Gurd’s original study came out was to report individual results rather than just an overall average. Let’s say you put a bunch of people through a 24-week training program tailored to their unique baseline fitness so that they all work equally hard and watch their VO2max increase by 10 percent (or in the units shown in the graph below , about 0.2 liters per minute), on average. That’s great, but not everyone raises by exactly 10 percent. Instead, you’ll see a number of individual responses like this (each bar corresponds to the change in VO2max of an individual subject):

On the right you have a very strong responder. In the middle you have the average of the respondents. On the left you have people who actually got less fit after 24 weeks of training. Shocking!

This idea of not responding to exercise gained a lot of attention in the early 1990s and led to a boom in personal training consulting, but it also drew backlash from statisticians. How do you know these variations are due to exercise, rather than measurement error or other lifestyle factors such as diet, sleep or stress? There is no way to tell from a graph like the one above. Instead, you need to compare these results to a control group that did nothing for the same amount of time.

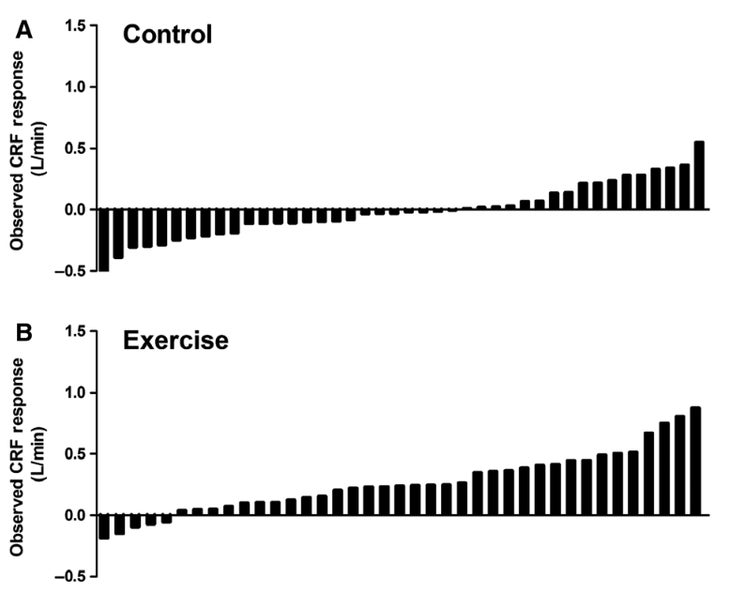

The vast majority of studies that purport to find responders and non-responders do not have an appropriate control group. The data above is from one of the rare studies that had a control group that did nothing for 24 weeks, reanalyzed by Gurd and colleagues in Physiological reports in 2019. This is what this data looks like:

We see exactly the same variation in response in the control and exercise groups. The only difference is that the exercise group is moved up with an average response of about 0.2 liters per minute. So the variation in response cannot be because some people “respond” to exercise (or specific prescribed exercises) while others do not—because subjects in the control group had similar responses to doing absolutely nothing.

New Data on Personal Training Consulting

Gurd’s new research, which was led by university student John Renwick and is published in Sports medicineruns a more rigorous version of this analysis on a massive data set drawn from 24 studies with 2,230 participants. This is every study they could identify in which subjects did a standardized and supervised exercise program, measured VO2max, and included a control group that did nothing.

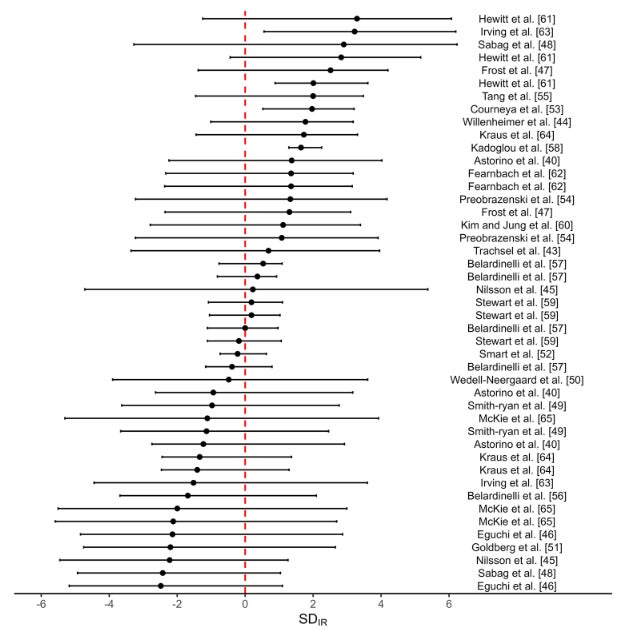

The primary analysis compares the standard deviation – a measure of the degree of individual variability in response – for changes in VO2max in the exercise group and the control group. If there is a true individual response to exercise, then the standard deviation should be larger in the exercise group than in the control group. If the standard deviations are the same, this indicates that the response is homogeneous between individuals.

Here are the results for 45 different tests (some of the studies included more than one training group):

The values to the right of the dashed line indicate that the standard deviation was larger in the exercise group. So the studies shown at the top of the graph appear to indicate individual variability in response. But the research at the bottom shows the opposite effect, seemingly (and nonsensically) suggesting that there is more variability in response to doing nothing than to exercise. There is roughly an equal number on either side of the line, and the error bars in almost all studies include the dashed line. Complete the statistics and the overall conclusion is that there is no evidence of inter-individual variation in response.

This conclusion does not come out of nowhere. After that initial research in 2016, Gurd realized before he looked for why some respond better to breaks and others to continuous training, he needed to better demonstrate that it was true. In one follow-up study, he essentially repeated the 2016 protocol except that the volunteers completed two like four-week training routines, separated by a three-month washout period. Once again, he found that some people responded best to the first training method and others to the second method—a clear sign that the change was not a result of the specific exercises prescribed.

And it’s not just endurance training and VO2max: numerous strength training studies and meta-analyses, such as this one by Solent University researcher James Steele and colleagues, have reached essentially the same conclusion using similar statistical methods. It goes against what we normally assume about how some people put on muscle more easily than others, and it even contradicts the results of a study I wrote about earlier this year that suggests some people benefit from do more sets of weight training while others benefit from sticking to fewer sets. More studies are planned to look for the elusive sign of individual response variability, Steele told me, “though at this stage I think it’s flogging a dead horse to try to look for it.”

What it all means

There are some very good reasons to think that variable responses to exercise exist. In the 1990s, a large research effort called the Heritage Family Study sought to determine whether individual genetics might influence how people respond to exercise. Indeed, they found that VO2max responses to training seem to cluster within families; Overall, they estimated that about half of the response to exercise is genetically determined.

There is also animal data, where successive generations of rats are bred to have little or no response to training. And then there is the other life experience of athletes. “I still believe there is a variation in response,” Gurd told me. “But we can’t prove it.”

If there is true variability in training response, however, it appears to be trivial compared to other sources of variability. One of the main ones is measurement error: if you are measured slightly below your true value on the baseline test and slightly above on the final test, you will look like a strong responder – and vice versa. There is also “within-subject variability”: changes in behavior or environment that have nothing to do with the exercise program being tested, such as sleep, diet or stress. These external factors may even be influenced by your genes, which could explain Heritage’s findings.

All of this might seem like bad news if you were dreaming of a bold new era of personalized training based on your unique training responses. But there’s great news if you want simple, practical exercise tips. The exercise programs and training principles that work best for the average person in large-scale studies, or that have been honed through decades of real-world experimentation by athletes and coaches, are almost certainly the same plans and principles that will work best for you. We are all individuals, but training is training.

For more sweat science, join me on Threads and Facebook , sign up for my email newsletter , and check out my book Endurance: Mind, body, and the curious elastic limits of human performance.

#Personal #training #waste #time #data #prove